Working on Fish Folk - Drifty

I didn’t update the blog too much these past months as most of my time was dedicated to bigger projects I couldn’t share too much about. However, this one in particular is getting a public reveal as I write this post so they gave me an OK to talk about it.

Fish Folk: Drifty is a kart racer with a half retro half cartoon aesthetic where little fish people drive funny bikes in pretty underwater environments. For the past few months I’ve been sponsored by Erlend of Spicy Lobster to make a prototype for what a racing game with their characters would look like, which could be used as a starting point for a Kickstarter campaign or a self funded project.

Making it into a commercial game is not part of my job, as this is supposed to be a proof-of-concept for a possible crowdfunding campaign, but it did mean I could explore aspects I hadn’t time to for my last racing game Project Nitro, such as design and AI, which was great. I also managed to get my friend Paulo Costa in to do the models and animations alongside the existing assets from other contributors of Spicy Lobster.

Game Design

By Erlend’s writing, Fish Folk games are supposed to be “really easy to play; no prior gaming experience required”, so the best reference material I picked is Mario Kart 8 Deluxe, one of Nintendo’s best selling games ever and for a reason. It has vibrant colorful visuals, an amazing live recorded soundtrack, strong “pick-up-and-play” design and a surprising amount of accessibility features for a japanese game. Me and my friends and relatives have poured hundreds of hours in that game’s splitscreen mode, and it was worth every penny, and capturing that quality and solidity into a project of mine is one of my goals here.

One of the aspects he also mentioned is “modding”, which I sadly don’t understand enough to capture in this prototype, but having seen amazing racing games which do feature modding, like Sonic Roboblast 2 Kart (which itself is a mod of a mod!), as well as the thriving community of custom tracks in games like Trackmania and Mario Kart Wii, I think there’s loads of potential to make such a game fresh and fun for a long time, as long as the base design and controls are great by themselves.

However, my approach in choosing what aspects to borrow and what to reinvent from other games was very conservative, as with the timeframe I had for this project, I didn’t really want to experiment with more unusual ideas that I had a hunch would take a lot to make work. So while I embraced some of the ideas Erlend suggested for mechanics, like drivers having a “balance meter” that let them take a few hits before flipping over, or being able to kick your opponents to drive them off-course, some ideas had me worried. One of the ideas pitched was drivers having to attack either stationary objects or little creatures on the track to get their items, and not only do I think that would make races more complicated than just focusing on driving and item usage, in my head it sounds very clunky as new players would be able to miss getting any items, and as drivers attack to their sides not the front, you’d have a think window to adjust your racing line and press the button. I instead went with simple item boxes for now.

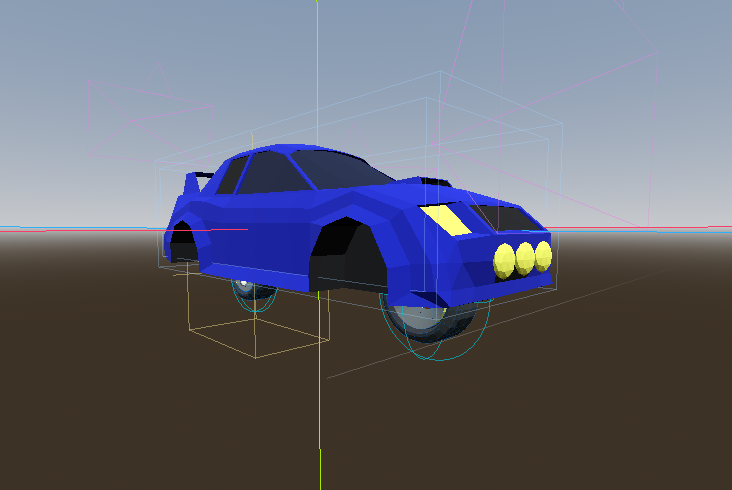

Physics

Although I could just have ported the racing physics I had at the start, I first tried to implement simplified versions of it, to better fit the arcade-y nature of the Fish Folk games as well as fit the bike handling a bit better. All my attempts of using CharacterBody3D failed miserably 😰. I then investigated code from my older projects and discovered Project Nitro had so many artificial constraints to keep the car from tumbling over (cars will rotate back to being straight up with time) that I could just build a car with two wheels. This does mean the new vehicles don’t enjoy going over half pipes or loop-de-loops but we don’t really need those for the track designs, so it’s fine.

Basing the driving model around constrained physics instead of fake physics does mean sometimes the bikes will still try to react like rigidbodies in conditions I haven’t accounted for, like pushing up walls or bouncing on stuff, but if all those situations can be recognized you can just apply more constraints to account for them. For example, the bikes would usually bounce off the floor after a big jump, which didn’t let you immediately drive forwards, so I addressed it by adding a second StaticBody below the bike with an absorbent physics material which would remove 90% of the bounce from the jump and let the bike keep driving right after landing.

Component Systems

I’ve often felt a bit lost when trying to figure the architecture of many of the game’s systems. By not having tutorials to follow it all feels like uncharted territory, and I’d say that’s one of the fun parts of software development in general, but it does have its ups and downs.

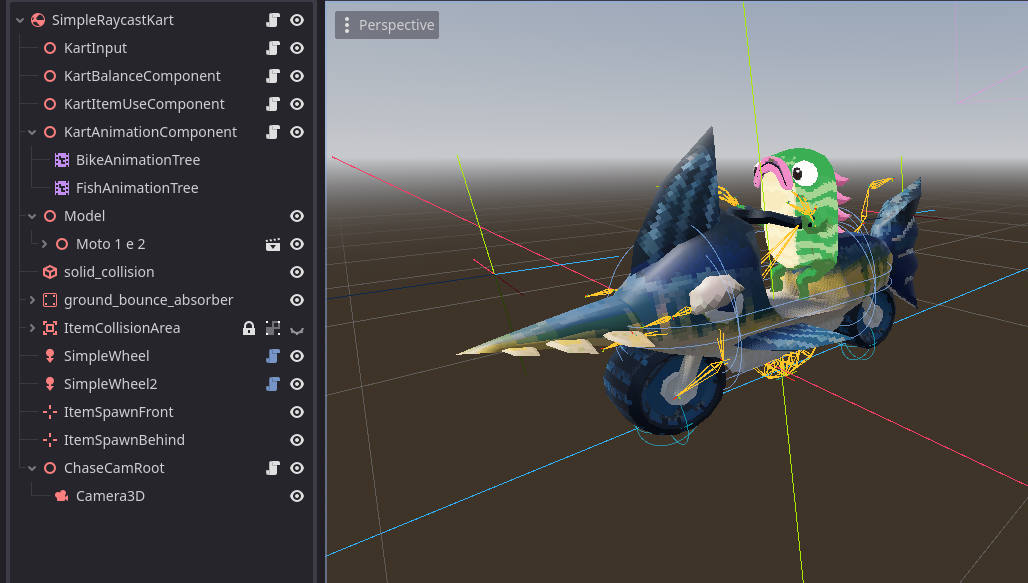

Godot is great at supporting composition-based architectures, so I experimented with that. Karts have different components to control animations, input and item use, which all could be swapped for different systems. But then I didn’t actually have different systems to swap between outside the inputs and the progress trackers, so that wasn’t a major selling point. Not shown here, but I actually think Godot groups work better than classes to determine if a certain node has a certain component, just because you can assign groups freely and quickly filter your tree with get_nodes_in_group.

I also gave up and delegated some of the logic to famous “Manager scripts”, for stuff like ranking karts according to race progress. I still have “components” to each track that individually handle spawning the karts, doing camera fly-arounds and managing checkpoints if there are any, but the Manager coordinates all of them. Overall, I think composition in Godot is worth studying, because it can lead to very powerful systems for more content-centric games, but a project like this can use some hard-coded aspects just fine.

CPU Drivers

This time I wanted to expand on what I did in Project Nitro and research how to implement non-player drivers, if at least to serve as powerup fodder, but mostly to liven up the prototype and to introduce the vehicular combat mechanics like balance and the melee attacks. I wrote a lot about my knowledge on AI-controlled drivers in racing games so far for future reference, but implementation is on the simpler side, especially since I haven’t yet studied artificial intelligence formally at the time of writing.

In summary, if a vehicle has an AI driver assigned to it, it can look at the track’s assigned racing path, project the vehicle’s current position onto it, look at the position a few meters ahead, and steer the vehicle left or right as needed. For sharp turns they also decelerate. This does have the side effect of making all drivers follow a single line through the course, for which a good fix hasn’t come to me yet.

I also intend on placing a few sensors to each side of the kart so they won’t stick to each other unless they intend to attack other drivers, and they especially avoid any possible walls on the track.

The Business Side

I’m not one to talk much about numbers and contracts but I’m not under any NDAs this time so I might as well do.

Erlend approached me via email after seeing both Project Nitro’s file on Github, as well as reading my blog post on it. I guess there just aren’t many open sourced racing game projects over there, I guess. We talked further via Discord, and his proposal was: he had a budget of 3000 dollars to develop a prototype of what a racing game with the Fish Folk would look like, and he could pay both Paulo and I $250 each for six months, and we’d work at what we deemed a reasonable rate for that value. For me, I deemed 8 hours a week for $250 was both around minimum wage in Brazil and enough work to fit with my schedule as a student.

It seemed like a great deal, as I did want an opportunity to expand on Project Nitro and research other aspects I ignored before, and I could work with Paulo as an artist. The only problem left was to estimate if I could balance the project with my studies, and for that Erlend suggested we first do a month to see if I can fit the project in my routine and reassess from there. I did, wasn’t too much of a struggle to fit, so I accepted the deal. I also closed in on getting paid after each month’s over, which my father later warned me against, but Erlend made all the payments on time so I hadn’t much to worry this time.

Challenges

One of my biggest barriers during this period was probably how technical debt started getting to me, as there were less things I could port over from Project Nitro and more things I had to research for myself. Not knowing exactly when to use and not to use composition also didn’t help much. I had to redo some aspects like input and rankings and have yet to redo powerups as I first wanted a quick proof-of-concept, but then other systems required those to be more versatile and as such, refactoring was needed. I mentioned the spaghetti code aready.

I also had to learn alongside Paulo how to make a reasonable workflow for both designing and modelling the race track, and during that process not only did I let Paulo draw the course layout while I implemented other systems, but he also finished a lot of the track’s assets before I tested the road and offroad sections, and as such I didn’t have the courage to ask for some tweaks I felt would improve the track later on because both his modelling and my importing and collision matching were taking longer than I wanted to. As such, some curves ended up a bit wonky and there’s an empty uphill straight I didn’t know how to spice up gameplay-wise.

In an ideal world, the artist would do concepts for the track’s theme, then the designer would sketch the layout, and then someone would graybox the layout and test and polish all the corners and sections before details are added. While I do have my own methods for grayboxing and modelling those tracks, not only am I not an expert, but other artists I know aren’t familiar with a few methods I use (like matching road slices to paths, or joining tris manually like it’s 1998). The graybox step is also important for making different geometries for physics and visuals, as often the collision shapes can be and often should be much simpler than their ingame models, for both game performance and physics predictability. This time around we didn’t do grayboxes but our models aren’t too complex so we used their original geometry for collisions too, as well as some invisible walls.

The last challenge was probably balancing development consistency after a routine change: some university classes were temporarily paralyzed for a few months halfway through the semester. This had me working on Drifty as well as some long-term uni assignments at home, which broke my well established routine and, with most of my friends either living far away or being workaholics like me, brought my day-to-day much closer to the 2020 status quo of being stuck at home with little social interaction or work discipline. Barely being a pandemic kid, I did not enjoy this, but tried to work it out anyway. I felt my productivity going way down, which had me feeling guilty about sitting to work on the racing game and not making much progress from research. Addressing that is an ongoing process which I have to deal with myself.

Closing Thoughts

I haven’t finished my time with Drifty yet, there’s a lot I’m still working on, but I do want to leave the project with a bunch of documentation, both on design and technical aspects so any future contributors aren’t majorly lost (my ugly code doesn’t help matters though haha). Another post about this project is planned, too.

I had an amazing time working on this project, it was very fulfilling and a great learning opportunity, I look forward to how this project will grow in the future, if the people at Spicy Lobster will take it somewhere, if they’ll make something unique.

Here’s the link to the Github repo if you wanna play or contribute to the project yourself.